British political parties are positioning themselves for an impending general election – but that doesn’t mean it will happen before Christmas.

The prime minister’s tactic of offering extra time for debating his withdrawal bill in exchange for an election date of December 12 is unlikely to work because opposition parties have every incentive to draw things out so that Britain remains in the EU after October 31. That will deprive the prime minister of the campaign slogan: “We delivered Brexit.”

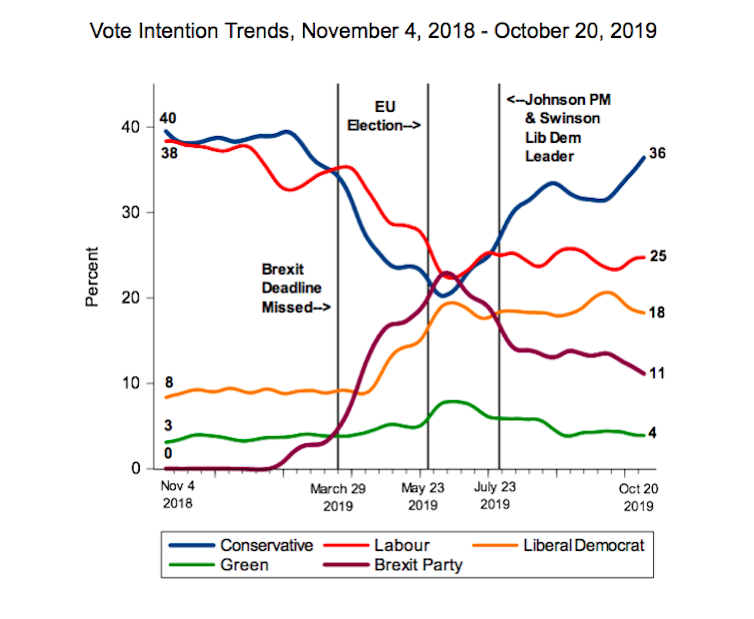

The Conservatives received a poll bounce after Johnson struck a Brexit deal and won his first parliamentary vote on the legislation underpinning it on October 19. Clearly they are anxious to profit from this by calling an early election before the bounce disappears. When Johnson became prime minister in July the party also received a boost, but this petered out by early September, suggesting that the life of the present bounce may be time limited as well.

Latest poll of polls. Paul Whiteley/Harold D Clarke, Author provided

To secure a majority, the Conservatives need to hoover up Brexit voters, just as Theresa May did in 2017 (one of her few successes that year). The UKIP vote fell from 12.6% in the 2015 election to 1.8% in 2017 and Johnson can’t afford to give any of that back to Nigel Farage and his Brexit Party.

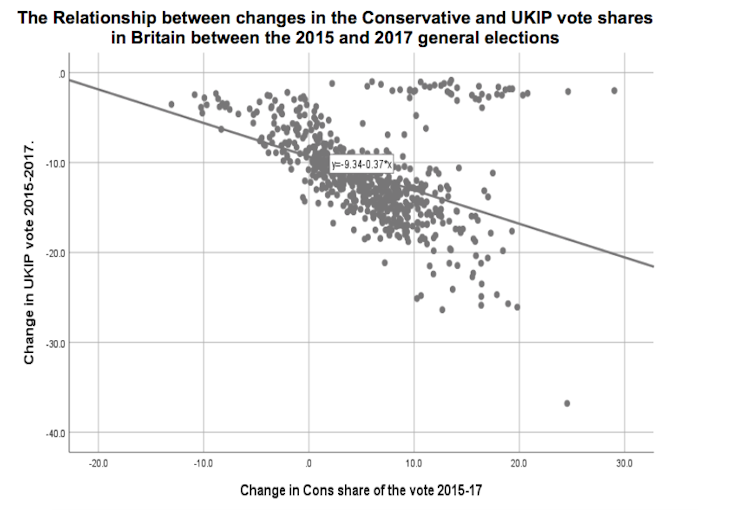

May’s remarkable achievement saved her government from losing the election. Each of the dots in the chart below is a constituency in Britain and the summary line shows that the change in the Conservative and UKIP vote shares were strongly (and negatively) related between the two elections. As the Conservative vote share rose the UKIP vote share fell. This negative correlation was actually stronger (-0.44) than the relationship between changes in the Conservative and Labour vote shares (-0.39), the traditional rivals in British party politics.

UKIP and the Tories, over time. Author provided

May was able to achieve this because her Lancaster House speech in January 2017 laid out plans for a hard Brexit. Her aim was to take Britain outside of the single market and the customs union and, at the same time, reject the jurisdiction of the European Court. UKIP supporters, most of whom had voted Conservative in the past, took May at her word when she declared “Brexit means Brexit” and duly voted for her party.

This poses the question as to whether Johnson can repeat this exercise in the case of the Brexit Party. Our simulations show that if he can capture the lion’s share of the Brexit vote he will easily win the next election with a comfortable majority. On the other hand, if the Brexit vote remains at its current level, then a hung parliament or a very small Conservative majority is likely.

Johnson faces a different situation to May. After threatening to leave without a deal he has now delivered a technically complicated withdrawal agreement which violates her red line by allowing a customs barrier to be created in the Irish Sea – a move that has alienated the DUP, his former allies in parliament. In addition he endlessly repeated the slogan that he will deliver Brexit by October 31 and would rather be “dead in a ditch” than ask for an extension.

Since that deadline is no longer possible, Farage and the Brexit Party will be poised to run a “Brexit betrayed” campaign in the election. In particular they will draw attention to the long period of time that Britain will remain in the EU during future negotiations. Finally, the deal fudges the issue of regulatory alignment with the EU and leaves the issue of whether or not the UK will be outside the customs union, in practice if not in theory, very vague.

The other problem the Conservatives face is that Labour is beginning to move ahead of the Liberal Democrats in the polls. As recently as the beginning of October the two parties were neck and neck in the polls, but the approaching general election highlights the Liberal Democrats’ perennial problem – that they are very unlikely to win an election. This means that Remainers who would like to see the present Brexit deal reversed or softened have to vote Labour if they want a party that can deliver.

New Liberal Democrat leader Jo Swinson’s political interests are not well served by seeing her party’s supporters drained off to Labour. This explains her offer, in conjunction with the SNP, to back an election on December 9. The quicker the election takes place the more likely the party is to sustain voting intentions support in double figures.

A long-game strategy for Swinson would be to let Labour “die in a ditch” in this election and then rally disaffected Labour moderates afterwards. Whether Swinson could keep her party’s supporters from moving to Labour remains to be seen. The desire of Remainers to keep Brexit at bay may push many of them to rally to Labour, even if his party’s position is unclear and even if it means tolerating the prospect of Jeremy Corbyn in Number 10. Corbyn is very unpopular with much of the electorate, but this may matter little in an election campaign dominated by the passionate politics of Brexit.

Trump Announces U.S. Strikes on Iran Navy as Conflict Escalates

Trump Announces U.S. Strikes on Iran Navy as Conflict Escalates  EU Urges Maximum Restraint in Iran Conflict Amid Fears of Regional Escalation and Oil Supply Disruption

EU Urges Maximum Restraint in Iran Conflict Amid Fears of Regional Escalation and Oil Supply Disruption  Middle East Conflict Escalates After Khamenei’s Death as U.S., Israel and Iran Exchange Strikes

Middle East Conflict Escalates After Khamenei’s Death as U.S., Israel and Iran Exchange Strikes  Pentagon Leaders Monitor U.S. Iran Operation from Mar-a-Lago

Pentagon Leaders Monitor U.S. Iran Operation from Mar-a-Lago  Pakistan-Afghanistan Tensions Escalate as Taliban Offer Talks After Airstrikes

Pakistan-Afghanistan Tensions Escalate as Taliban Offer Talks After Airstrikes  Netanyahu Suggests Iran’s Supreme Leader Khamenei May Have Been Killed in Israeli-U.S. Strikes

Netanyahu Suggests Iran’s Supreme Leader Khamenei May Have Been Killed in Israeli-U.S. Strikes  Macron Urges Emergency UN Security Council Meeting as US-Israel Strikes on Iran Escalate Middle East Tensions

Macron Urges Emergency UN Security Council Meeting as US-Israel Strikes on Iran Escalate Middle East Tensions  Argentina Senate Approves Bill to Lower Age of Criminal Responsibility to 14

Argentina Senate Approves Bill to Lower Age of Criminal Responsibility to 14  Israel Strikes Hezbollah Targets in Lebanon After Missile and Drone Attacks

Israel Strikes Hezbollah Targets in Lebanon After Missile and Drone Attacks  Trump Says U.S. Combat Operations in Iran Will Continue Until Objectives Are Met

Trump Says U.S. Combat Operations in Iran Will Continue Until Objectives Are Met  Israel Declares State of Emergency as Iran Launches Missile Attacks

Israel Declares State of Emergency as Iran Launches Missile Attacks  Germany and China Reaffirm Open Trade and Strategic Partnership in Landmark Beijing Visit

Germany and China Reaffirm Open Trade and Strategic Partnership in Landmark Beijing Visit  Trump Says U.S. Attacks on Iran Will Continue, Warns of More American Casualties

Trump Says U.S. Attacks on Iran Will Continue, Warns of More American Casualties